Everyone has seen football players change direction at high-speeds. Often these moves create game-changing situations. The ability to rapidly and proficiently change sprint direction, or multidirectional speed, is a highly-regarded athletic quality. There are two types of tasks that encompass multidirectional movement, change of direction tasks and agility tasks. Being able to train specifically for these movements gives athletes the ability to perform at high levels in both predictable and unpredictable game situations.

Change of Direction Tasks involve changes in sprint direction that require limited response thinking because they are performed in a predictable or unchanging environment. Examples are ladder/hurdle drills, 5-10-5 drill, or even a wide receiver running a route without a defensive player guarding them. In these examples the cones that signal a directional change or the non-defended route are predetermined and predictable. Since the environment and stimulus do not change, these movements require minimal thinking or reaction.

Agility Tasks involve changes in sprint direction in an unpredictable or changing environment. These movements are considered to be more sport-specific and vary depending on the game and actions of other players. Examples are offensive and defensive players participating in drills such as a quarterback and wide receiver versus a defensive back, 7-on-7, and 9-on-7. In these examples, though there are predetermined “assignments” each player must execute, their movements will be largely dependent and adjusted in response to their opponent(s).

Enhancing performance in both change of direction and agility tasks involves resistance training and training drills that force athletes to change directions while the athlete is in postures and situations that are frequently experienced in their sport.

Enhancing performance in both change of direction and agility tasks involves resistance training and training drills that force athletes to change directions while the athlete is in postures and situations that are frequently experienced in their sport.

Improving performance in change of direction tasks requires a strength foundation to effectively cope with greater angles of direction change (e.g. a 180-degree direction changes), while speed-strength (“power”) is needed for smaller angles (e.g. a 20-degree direction changes). For agility tasks both strength and speed-strength are needed. However, improvement requires placing athletes in situations that force them to “read and react” to game-like situations, opponent body language and other changing external cues.

Ideally, training would begin with resistance training intended to improve strength and speed-strength, while including change of direction tasks that contain postures and movements frequently experienced in the sport. Once athletes become proficient in these tasks training should quickly progress to agility tasks that put the athletes in more sport-specific environments and situations. Using this progression will improve athleticism and responsiveness needed to make that mind-body shift that could decide whether a play wins or loses the game.

About the Author

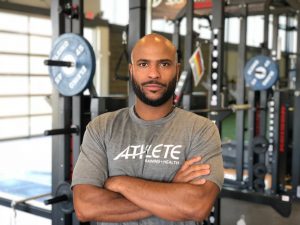

This article was authored ATH Arlington’s Director of Athletic Performance, Frank Bourgeois, PhD, CSCS. Frank recently earned his PhD at Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand in their Sports Performance Research Institute (SPRINZ).Frank earned his M.S. in Exercise Physiology at Midwestern State University and his B.S. in Biology from Morehouse College. During his career he’s contributed to the enhanced performance of athletes at several schools.His applied research extends into several areas, with emphasis on speed and the role strength and power play in change of direction.

This article was authored ATH Arlington’s Director of Athletic Performance, Frank Bourgeois, PhD, CSCS. Frank recently earned his PhD at Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand in their Sports Performance Research Institute (SPRINZ).Frank earned his M.S. in Exercise Physiology at Midwestern State University and his B.S. in Biology from Morehouse College. During his career he’s contributed to the enhanced performance of athletes at several schools.His applied research extends into several areas, with emphasis on speed and the role strength and power play in change of direction.