Blog by Nikki Simmons and Meredith Sorensen, MS, RD, LD

Meredith Sorensen is a performance dietitian for Memorial Hermann Rockets Sports Medicine Institute and former collegiate distance runner for the University of Houston. Nikki Simmons is a dietetic intern whoassisted with this project.

Running a marathon takes time, preparation, and knowledge for successful completion. Both training and nutrition play a role in preparing for your race. Marathon races take anywhere from 2 to 6 hours to complete, and your body requires a great amount of energy to support this effort. During the race, the main sources of energy are carbohydrates and fats. In order to maximize potential performance on race day, it is important to optimize the body’s storage of these fuel sources to prevent or delay “hitting the wall” or “bonking”. Individualized fueling strategies consist of many components and vary depending on personal preferences and tolerance to fueling strategies.

SPECIAL OFFER!

Runners located in the Katy area – Are you hoping to run your fastest all while being well-fueled and pain-free? Check out the Strength and Nutrition for Runner’s Workshop being held from 11/28-1/8 at the Memorial Hermann Sports Park, co-hosted with Athlete Training and Health. In addition to receiving a virtual nutrition class and an individualized nutrition consultation, you can partake in two weekly in-person lifts geared toward improving running economy. For more information contact:

Pre-Race Nutrition: The Day Before

The duration of the marathon increases the body’s demand for carbohydrates, and a runner should account for this prior to the race. Before the race, many athletes undergo “carb loading”, the process of fueling up with higher-than-normal amounts of carbohydrates for a short period of time prior to the race. This practice is aimed at increasing stored energy (glycogen) in the liver and muscle to be more readily available during the race. It takes time for the body to store these carbohydrates, which is why the process is recommended to start around 24-36 hours before the race. This strategy focuses on easily digested carbohydrates such as breads, pasta, cereals, juice, which have been shown to improve race performance by prolonging the amount of time race pace can be maintained.[1]

Instead of overloading the body with carbohydrates in one or two meal sittings prior to your first strides of the race, it is recommended to use this time to space these higher carbohydrate fueling sessions 2-3 hours apart during the loading period. This gives your stomach time to digest, absorb, and utilize everything you are consuming. Your diet does not, and should not, drastically change in the days prior to your race. Instead, focus on items you can easily add into your diet that will provide those easily digestible carbohydrate sources. For example, adding those into regular meals could look something like this:

- Breakfast: eggs + toast + juice

- Lunch: sandwich + banana + crackers

- Dinner: roasted chicken + potatoes + green beans

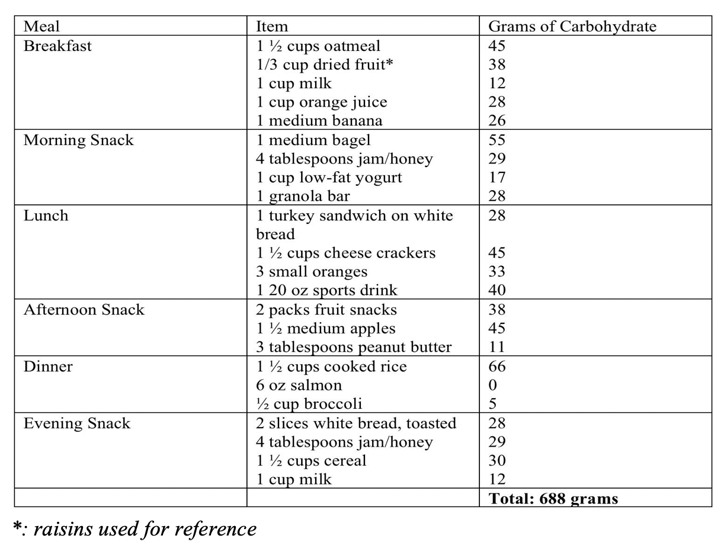

Carbohydrate loading recommendations are dependent on the level of intensity and duration of the exercise as well. It is recommended that “carb loading” should consist of 8-12 grams/kilogram of body weight daily. Of course, this number means nothing if we do not know what to do with it. So let's take a 150 lb (68 kg) athlete training alongside you for the upcoming marathon. With the recommendation for “carb loading” in mind, this means the athlete needs somewhere between 540-810 grams of carbohydrate the day before the race to adequately “carb load”. A day in the life of this athlete providing the necessary energy for race day to properly “carb load” would look something like this:

Proper fueling for the race can look different for everyone depending on tolerance and preference. It is important to find what you like and what works best for you. For those who are more nervous on race day and struggle to fuel up, incorporating “carb loading” may be a necessary strategy to ensure adequate energy is available for the body.

Pre-Race Nutrition: The Day of the Race

The practice of “carb loading” helps to successfully prepare for the marathon ahead, and proper fueling should continue on race day. The liver and muscle store carbohydrates in the form of glycogen that can be utilized for the race. After a night of rest, liver glycogen stores become reduced by about 40% and require “topping off” to help maintain energy levels throughout the race. “Topping off” is the practice of consuming easily digestible carbohydrate sources a few hours before the race to replenish glycogen lost during sleep. It is recommended that athletes consume anywhere from 1-4 grams/kilogram body weight of carbohydrates 1-4 hours before the race.

The general rule of thumb is to consume 1 gram/kilogram of carbohydrates for every hour prior to the race (i.e. 1 hour before the race would be a carbohydrate fueling of 1 grams/kilogram, 2 hours would be 2 grams/kilogram, etc.). It is important to note that this does not mean fueling up every hour on the hour with these recommendations. Research has shown that a single dose of carbohydrates in the 1-4 hours before the event is sufficient to replenish glycogen stores.

Eating in the few hours before the race depends on personal preference and tolerance. It is important to know what works best for you and how your stomach handles these foods when running a marathon. If you already know that consuming large amounts of food does not work well before a long run, try liquid forms of carbohydrates such as gels or sports drinks for faster clearance and easier tolerance. Consuming a higher amount of carbohydrates can be difficult for some athletes which is why it is helpful to start introducing these earlier in your training and taking them at your own pace. This gives your body time to adjust and know what to expect on race day.

There are also foods to avoid or limit on race day. These are typically foods that you have not tried/experimental foods, foods that do not sit well in your stomach, high fiber foods (i.e. oat bran muffins or apples), high fat foods (i.e pastries or donuts), and high protein foods (i.e. protein bar or tuna). Each and every runner will have different tactics for fueling up on race day. Keep in mind that your body takes some time to adjust to new habits and find what works best for you. The point is to give your body the energy it needs for the entirety of the race.

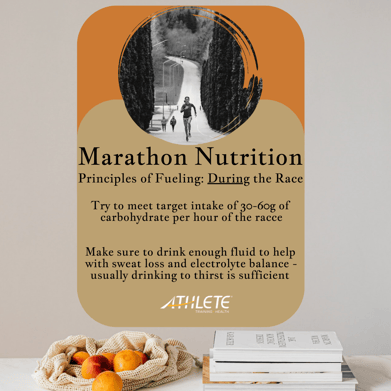

During Race Nutrition

Due to the long-lasting nature of running a marathon, it is important to continue to fuel your body during the race. Fueling up properly mainly focuses on having carbohydrates during the run, but guidelines for protein and fluid have also been studied in relation to performance.

Carbohydrates:

Ingesting carbohydrates during the race can help to maintain energy levels and blood sugar throughout the entirety of the run. Generally, simple and quick carbohydrates like gels and sports drinks do the trick. It is recommended to consume 30-60 grams per hour of carbohydrates during long duration exercise such as a marathon. This recommendation comes from the understanding that the body can only absorb and utilize up to about 60 grams/hour of carbohydrates. Above 60 grams/hour, the intestines struggle to absorb anything more without proper training of the gut. It may be easier for those who are introducing carbohydrate intake into their runs to start out on the lower end of the recommendation. Longer durations and consistent practice of fueling during endurance exercise may result in better tolerance of the higher end of the recommended carbohydrate intake. This fueling method should not be started on race day if your gut has not been routinely exposed to this method of fueling during a run. When practicing this strategy before the race, it can be helpful to practice fueling like race day for your body to adjust and know what to expect.

Having carbohydrates during the race will also help to maintain blood sugar levels and make sure the body does not use too much of the glycogen stored in the liver. Ensuring provision of carbohydrates can help to maintain blood flow to the gut and limit gut damage that occurs during extended periods of exercise. To accomplish these things, fueling should start within the first hour of the race.

Protein:

Protein supplementation may be warranted during exercise. This is generally not recommended for everyone and it takes preparation ahead of time for the body to adjust to protein during endurance exercise. Recommendations are 0.25 grams/kilogram of protein per hour with carbohydrates. Research has shown that having protein with carbohydrates can help to suppress markers of muscle damage for 12-24 hours after endurance exercise such as a marathon.[2]

Fluid:

During the race, make sure you are taking in enough fluid without overdoing it. The body likes to keep electrolytes like sodium and potassium within certain ranges. The concentration of these electrolytes can become imbalanced if too much fluid is consumed, which can cause serious impairments in performance. When ingesting too much fluid during exercise, athletes can develop “exercise associated hyponatremia” which means that the fluid intake (drinking water, sports drinks, etc.) exceeds output (urination, sweat, expiration of breath, etc.) and causes a reduction in the concentration of sodium in the blood. Symptoms of exercise associated hyponatremia include weakness, headaches, dizziness and nausea/vomiting. In order to prevent this from happening, keep an eye on the following: urine color (it should be similar to a pale lemonade color), any feelings of dehydration (feeling dizzy or lightheaded, dry mouth) and level of sweating. Your body does a good job of telling you when you need to drink, so it is good practice to listen to your thirst signals.

Post-Race Nutrition:

After running a marathon, it is helpful to remember the three R’s of recovery: replenish, repair, rehydrate.

Replenish:

After the race, carbohydrate stores have been depleted and will need to be replenished. Replenishing with carbohydrates will look different for every athlete based on their preferences and what they can tolerate. Having carbohydrate sources that are easily digested in the body soon after the race can help with replenishing energy stores. These could be things like fruit snacks, pretzels, fruit juice and/or a sports drink. Your appetite will most likely be decreased after completing the race which mainly comes from the significant amount of gut damage that occurs. Therefore, it may be helpful for refueling purposes to consider these more easily digested carbohydrates sources.

In the following hours, having a post-race meal will help to continue replenishing the energy used in the race and begin repairing some of the muscle damage incurred. The post-race meal should still have a high amount of carbohydrates and some protein included. This could be something like chicken, pasta, broccoli and garlic bread. The amount of carbohydrates consumed in the 24 hours after the race should still be high (about 8-10 grams/kilogram), so having a few different kinds of carbohydrates in the meals after the race will help replenish glycogen stores.

Repair:

Studies have shown that the body is more sensitive to protein ingestion and muscle protein synthesis post-exercise. In the 24 hours following exercise, the body can use protein more efficiently to repair muscle damage caused during the race.

Recommendations for protein post-exercise are 0.25-0.3 grams/kilogram (about 17-20 grams for a 150 lb athlete) of a quality protein source in the 0-2 hours after the race. Quality protein sources include, but are not limited to, meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy. Proteins rich in leucine are most effective at stimulating the muscle repair process. Leucine-rich options include: chicken breast, roasted pumpkin seeds, and Swiss cheese. Providing the body with the type of energy it needs to help repair muscle may help with recovery after the race.

Another time when protein is vital after a race is when carbohydrate ingestion is sub-optimal. As discussed, appetite will likely be low after the race and you may not want to eat much. If sufficient carbohydrates cannot be consumed post-exercise, you can add in some protein sources to help give the body the calories it needs to repair muscle damage and replenish fuel stores in the muscles. If the lower end of the recommendation for carbohydrate ingestion is being met (1.2 grams/kilogram/hour), adding in protein will not further increase glycogen synthesis. It is uncertain whether protein provision with carbohydrates can help with reducing muscle damage or soreness and the optimal ratio remains to be determined.

Rehydrate:

Recommendations for rehydrating post-exercise are to drink 150% of the fluid lost based on body weight change before and after the race. The body continues to lose fluid after the race (i.e sweating, urination, etc.), so fluid losses do not end when the race does. This is why the recommended fluid replacement is higher than what is lost. To assess fluid loss during a race, weigh yourself before the race while wearing dry, loose-fitting, lightweight clothing and after going to the bathroom. After the race, dry off and remove any sweat-soaked clothing and weigh yourself again to determine the change. For every pound lost during the race, you should replace it with 20-24 oz of fluid which is generally achieved with drinking as desired after the race and with food. Personalizing your fluid intake related to thirst and your individual losses can help you recover without the risks of over-hydrating.

Interested in learning more? Would you like to receive more personalized nutrition recommendations? E-mail Meredith.Sorensen@memorialhermann.org and mention this blog post!

SPECIAL OFFER!

Runners located in the Katy area – Are you hoping to run your fastest all while being well-fueled and pain-free? Check out the Strength and Nutrition for Runner’s Workshop being held from 11/28-1/8 at the Memorial Hermann Sports Park, co-hosted with Athlete Training and Health. In addition to receiving a virtual nutrition class and an individualized nutrition consultation, you can partake in two weekly in-person lifts geared toward improving running economy. For more information contact:

Sources:

- Alghannam, A. F., Ghaith, M. M., & Alhussain, M. H. (2021). Regulation of Energy Substrate Metabolism in Endurance Exercise. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(9), 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094963

- Burke, L. M., Millet, G., Tarnopolsky, M. A., & International Association of Athletics Federations (2007). Nutrition for distance events. Journal of sports sciences, 25 Suppl 1, S29–S38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410701607239

- Casazza, G. A., Tovar, A. P., Richardson, C. E., Cortez, A. N., & Davis, B. A. (2018). Energy Availability, Macronutrient Intake, and Nutritional Supplementation for Improving Exercise Performance in Endurance Athletes. Current sports medicine reports, 17(6), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000494

- Ormsbee, M. J., Bach, C. W., & Baur, D. A. (2014). Pre-exercise nutrition: the role of macronutrients, modified starches and supplements on metabolism and endurance performance. Nutrients, 6(5), 1782–1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6051782

- Vitale, K., & Getzin, A. (2019). Nutrition and Supplement Update for the Endurance Athlete: Review and Recommendations. Nutrients, 11(6), 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061289

- Rothschild, J. A., Kilding, A. E., & Plews, D. J. (2020). What Should I Eat before Exercise? Pre-Exercise Nutrition and the Response to Endurance Exercise: Current Prospective and Future Directions. Nutrients, 12(11), 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113473

- Millard-Stafford, M., Childers, W. L., Conger, S. A., Kampfer, A. J., & Rahnert, J. A. (2008). Recovery nutrition: timing and composition after endurance exercise. Current sports medicine reports, 7(4), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0b013e31817fc0fd

- Lambert, E. V., & Goedecke, J. H. (2003). The role of dietary macronutrients in optimizing endurance performance. Current sports medicine reports, 2(4), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1249/00149619-200308000-00005

- Jeukendrup A. (2014). A step towards personalized sports nutrition: carbohydrate intake during exercise. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S25–S33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0148-z

- Podlogar, T., & Wallis, G. A. (2022). New Horizons in Carbohydrate Research and Application for Endurance Athletes. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 10.1007/s40279-022-01757-1. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01757-1

- Hawley, J. A., Schabort, E. J., Noakes, T. D., & Dennis, S. C. (1997). Carbohydrate-loading and exercise performance. An update. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 24(2), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199724020-00001

- McDermott, B. P., Anderson, S. A., Armstrong, L. E., Casa, D. J., Cheuvront, S. N., Cooper, L., Kenney, W. L., O'Connor, F. G., & Roberts, W. O. (2017). National Athletic Trainers' Association Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for the Physically Active. Journal of athletic training, 52(9), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-52.9.02

- Nutrients: Leucine (G) - USDA. United States Department of Agriculture. (2018). Retrieved November 8, 2022, from https://www.nal.usda.gov/legacy/sites/default/files/leucine.pdf