By: ATH Performance Coaches Aubrey Carroll, BS, and Mac Graham, CSCS

Train Hard, Recover Harder

These days individuals of all ages are engaged in either general wellness or strength and conditioning programs to enhance strength and movement qualities. With the heightened push from medical and sports science practitioners to improve quality of life and increase the likelihood of success in sport, physical activity – whether casual or systematic – is becoming a normal part of daily life for many individuals. However, the eagerness generally accompanied by the ambition to improve cardiopulmonary and neuromuscular function can often times lead to a routine that lacks appropriate rest to allow the body to recover and prepare for the next bout of exercise.

The purpose of this blog is to discuss the basic physiological principles that underpin training; whether for general health and fitness or for high-performance in competition. This should give insight into why the need for recovery manifests. Also discussed is when recovery within a training regimen, in general, may be needed. A secondary aim is to provide common, yet effective, methods of recovery that can be easily incorporated into a daily routine.

From a physical conditioning perspective, the body can be viewed as a biological machine that receives input and generates an output. However, unlike most machines, the body has the innate ability to adapt to physical stress imposed on it to improve its function.

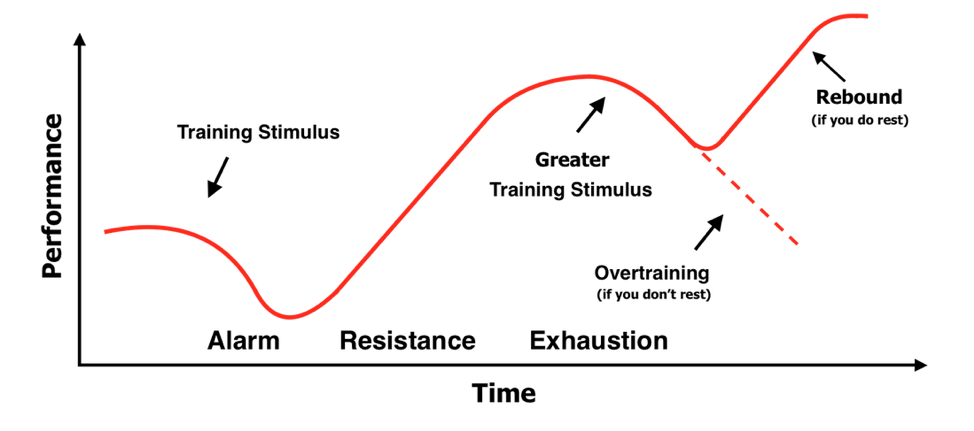

Ultimately, the aim of training is to introduce a specific stimulus termed “stress” to encourage a response termed “strain” [Brooks et al., 2005]. It is this time-sensitive relationship (i.e. stress and strain) that affords the adaptation advantageous for activities of daily living as well as competition. The stress-strain-response phenomenon was coined by Dr. Hans Selye [1950] as GAS, or the General Adaptation Syndrome. This process consists of three phases – alarm reaction, resistance development and exhaustion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General adaptation syndrome. This describes the stress-strain-response of training.

Briefly, the alarm reaction phase is the initial response to training. This is where the ‘system’ begins to prepare itself for near-future training (or ensuing stresses). As noted in Figure 1, the initial stimulus “shocks” the athlete resulting in intense soreness and a general decline in performance.

Next, the athlete transitions out of the alarm phase largely due to a phenomenon called the repeated-bout effect [Nosaka et al., 2001]. This effect is widely considered a protective mechanism that attenuates the “shock” associated with the initial phase of exercise (e.g. soreness, loss of strength and range of motion, etc.). With an enhanced ability to cope with greater stresses, training becomes more intense and places a greater amount of stress on the athlete. This represents the ultimate goal of training – the resistance development phase. This phase encourages an adaptive response as opposed to a ‘shock’ response.

However, as training intensity continues to increase, the athlete may begin to feel like they have hit a wall. This is known as the exhaustion phase; where training stress is considered harmful, and if not addressed appropriately the athlete runs the risk of overtraining. The overtraining phase is where the stress becomes extremely harmful – that is, increased risk of injury and mental burn-out [Koutedakis and Sharp, 1998; Kreher and Schwartz, 2012].

How do I reach Exhaustion?

- Your point of exhaustion will be dictated by how many years you have been training (i.e. training age). For example, beginners and novices tend to encounter it sooner and potentially more frequently, while more experienced individuals tend to encounter a later onset and potentially less frequently.

- Exhaustion is typically seen in individuals after 3-4 weeks of intense training has been achieved. This can vary from athlete to athlete, and is dependent upon training frequency and on how serious they are taking their recovery.

How do I know if I am Overtrained?

Are you experiencing:-

- Lack of motivation and general exhaustion

- Anxiety or depression

- Prolonged soreness

- Plateau or decline in performance

- Difficulty sleeping

These are common signs of overtraining [Kreher and Schwartz, 2012; Budgett, 1998]. Learning to recognize these symptoms early will help you become familiar with when and how you need to incorporate a deload in your training program.

When and how should I deload or unload?

- We recommend a consistent restoration phase every 2-4 weeks depending on your training age.

- These phases will typically last a week, where you take a step back from the loads you are using, or reduce the total volume you'r using, and also the amount of rest you allow throughout your workout.

Methods of Recovery

When it comes to methods of recovery outside of the training program, the question that should be posed is “What are you doing the other 22 hours of the day?” At ATH we provide a concept called AREA 22. This is a designated area within our training centers where we suggest different ways to make the best use of those 22 hours around the typical 2-hour training session. The information provided addresses daily habits, as well as activities that may be most effective at a certain moment in time. Basic recovery methods we encourage at ATH involve:

Primary methods [Hausswirth and Le Meur, 2011; Fullagar et al., 2015; Kreher and Schwartz, 2012]:

-

- Well-balanced diet and proper hydration

- Getting enough sleep

Secondary methods [Highton and Twist, 2015]:

-

- Dynamic stretching

- Low-intensity cardio exercise

- Low-intensity full range of motion lifts

- Soft tissue modalities (e.g. myofascial release)

Tertiary methods [Highton and Twist, 2015]:

-

- Cryotherapy

- Compression

- Massage

Key Takeaways

In summary, when undertaking an exercise routine be sure to incorporate periods of rest to allow recovery. In general, the greater the intensity incurred, the greater the recovery. When you enter phases of intense exercise be mindful of the typical signs of overtraining – for example, prolonged soreness or a plateau in performance. In addition to programming deload or unload weeks into your training regimen, simple activities such as dynamic stretching, low-intensity exercise and massage can be easily added to your daily routine to assist in the recovery process.

References

- Brooks GA, Fahey TD, Baldwin KM. Exercise Physiology: Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications – Fourth edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

- Budgett R. Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndrome. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;32:107-10.

- Fullagar HKH, Duffield R, Skorski S et al. Sleep and recovery in team sport: current sleep-related issues facing professional team-sport athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2015;10:950-7.

- Hausswirth C, Le Meur Y. Physiological and nutritional aspects of post-exercise recovery specific recommendations for female athletes. Sports Medicine. 2011;41(10):861-82.

- Highton J and Twist C. Recovery Strategies for Rugby. In: Twist C, Worsfold P, editors. The Science of Rugby: New York, NY: Routledge; 2015. P. 101-16.

- Kreher JB, Schwartz JB. Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health. 2012;4(2):128-38.

- Koutedakis Y, Sharp NCC. Seasonal variations of injury and overtraining in elite athletes. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;8:18-21.

- Nosaka K, Sakamoto K, Newton M et al. The repeated bout effect of reduced-load eccentric exercise on elbow flexor muscle damage. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001;85:34-40.

- Selye H. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. British Medical Journal. 1950;1(4667):1383-92.